17 ways to Sunday: Darrell Waltrip’s ’89 500 win, its freaky numbers connection and lasting legacies

Darrell Waltrip had all sorts of numbers in his favor before the 1989 Daytona 500. The signs and signifiers all added up. To this day, he still says he doesn’t necessarily subscribe to the belief that numbers have some higher mystique.

And yet …

“I really don’t,” Waltrip says. “It just so happens that when you’re driving car No. 17 and it’s your 17th Daytona 500 and you just kind of start looking at all the possibilities. My name (Darrell Lee Waltrip) has 17 letters in it. Our house is actually built on lot No. 17. My golf handicap is 17. The purse was $1.7 million. It was ’89 — 8 and 9 … 17.”

Those coincidences were too numerous to miss, so many that Waltrip pulled crew chief Jeff Hammond aside to discuss them before the race. Would those recurring 17s would be a promising bellwether or an ill-fated omen?

“So many things added up to 17,” Waltrip said. “And I’ve said this before, I told Hammond, I said, ‘I think there’s some good things happening here. We’re either going to win it or we’re going to finish 17th. I’m just not sure which.”

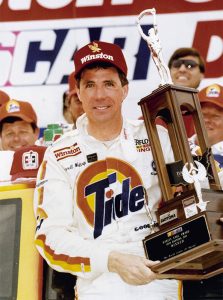

When it came to the finishing order, the cosmic number 17 stopped there. Darrell Waltrip’s long-sought Daytona 500 victory was a dream come true on Feb. 19, 1989, thanks to a strategic gamble, a car named Betty and a fuel-sipping final run to the checkered flag. The completion of his career bucket list touched off a stirring celebration, one marked by a memorable, incredulous Victory Lane interview and a triumphant dance tied to a brief NFL fad.

RELATED: Ranking every Daytona 500

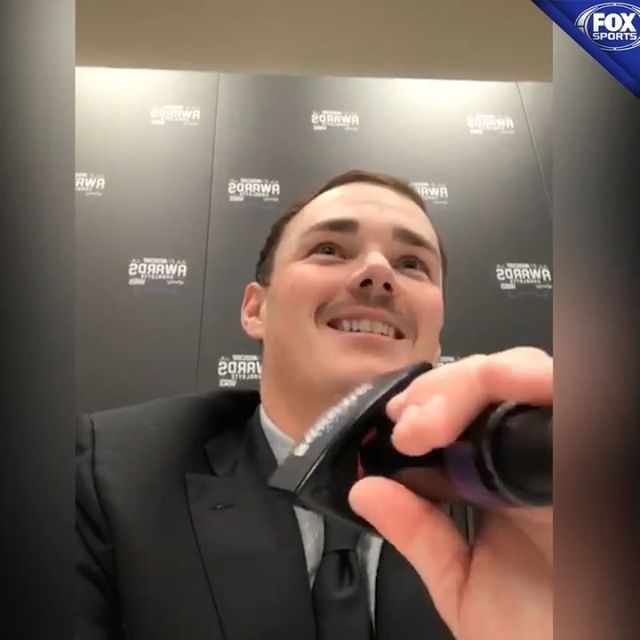

Thirty years later, the connective tissue that binds many of that day’s prominent figures still resides in the FOX Sports booth. Waltrip and Hammond continue to be teammates, now entering their 19th season of full-time broadcasting. They’re anchored by play-by-play expert Mike Joy, who conducted that highlight-reel post-race interview, and joined by Larry McReynolds, like Hammond a member of that era’s tight-knit community of crew chiefs.

The story of that day still rings true today, united by their continued work as teammates.

Finding their way

Waltrip had qualified his lucky No. 17 on the front row, starting alongside pole-sitter and Hendrick Motorsports teammate Ken Schrader. His car, supplied with power from legendary engine builder Randy Dorton, carried so much speed that Waltrip said the crew installed a smaller restrictor plate for preseason testing so as not to fully show their hand. It’s what fed Hammond’s optimism that year, even though the car’s bouts of misfortune the previous season left the window open for doubt.

“Honestly, coming into that year, I was very confident,” Hammond said. “The car that we were going to run had been built the year before — a really good, fast race car. We had a lot of bad luck in that car, which if you don’t know, was named Betty. Darrell had named that car Betty, and he liked to go around saying, ‘Betty’s being bad.’ ”

Changes with tires and other set-up issues reared up the car’s more finicky side, something that Hammond and the No. 17 crew battled throughout race day.

“There were a lot of very strong cars at Daytona that year and a number of leaders late in the race,” Joy recalled, “so certainly you would’ve put Darrell among the favorites, but he was not an overwhelming favorite to win. All of those Hendrick cars were strong. At the start of the race, I wouldn’t say that he was the favorite, but he had made it very clear to everybody that he was going to be a contender.”

Instead, it was a veteran teammate in Schrader who set the pace, leading the majority of the race and running in close competition with Dale Earnhardt, who would have his own storied chase of an elusive 500 crown fulfilled nearly a decade later. All the while, Waltrip lingered in the hunt.

RELATED: Darrell Waltrip through the years

“During the race, we kept working, working, working and we’d kind of gotten off sequence,” Hammond said. “We had done our homework and we knew we were getting good fuel mileage. We’d started to do some calculating from the end of the race back to where we were. At that point in the race, we were kind of chasing these guys, but then realized that we have an opportunity here if we can stretch it on this next stop that we can make it on one more stop, and that if this thing stays green, we’re going to be in the catbird seat.”

Groundwork to the gamble

The foundation for a winning strategy started well before the 500-miler. Back then, fuel tanks were larger and the qualifying races were shorter — 125 miles — meaning teams planned to compete in those races without stopping for fuel. To make absolutely certain, Hammond said his team pushed to the maximum allowable size on fuel lines, overflow tubes and anything else related to the fuel system.

“We were able to take what was legally at our discretion and we maximized it,” Hammond said. “All of a sudden, we’re adding ounces to our capacity.”

Those extra drops would come in handy. Decision time came with 53 laps to go, but it wasn’t solely the crew chief’s call to make. In the pit area alongside Hammond was Waltrip’s devoted wife, Stevie, who kept a record of lap times and fuel calculations.

“The gas was going to be really close,” Stevie Waltrip said. “I can remember Jeff and I talking and trying to decide should we pit, because we knew how close it was going to be. I told Jeff, ‘Look, we know how to lose this race. Let’s go for it.’ So we did.”

MORE: Read up on this year’s race

Said McReynolds: “I think she was as much on board with what was going on here and I think she knew the situation, too. This is the biggest race of the year, it’s a stretch, but it’s doable and heck, let’s roll the dice here. Let’s go after it. I commend Darrell and Jeff and Stevie, the engine guys, and everybody involved with that for basically being all-in and pushing all their chips to the middle of the table.”

The final stretch

One by one, other contenders peeled off the track for small doses of fuel. Prime among them were front-runners Schrader and Earnhardt, who pitted together with 11 laps remaining. That left Alan Kulwicki and Waltrip, who used every aerodynamic draft aid he could to ease the burden on his accelerator pedal.

“We had told him what we were doing, so he had started conserving fuel early in that final run,” Hammond says. “I even told him one time, man, you draft anything you can get behind, including a seagull.”

Kulwicki dropped off the pace with four laps remaining, pitting with what was later revealed to be a flat tire, not a fuel issue. That left just Waltrip, hemmed in to the strategy that would carry his Tide-sponsored No. 17 Chevrolet to the end.

“We didn’t have fuel pumps like they do now, it’s gravity-fed, you could get fuel on the straightaway and lose it in the corners, so I’m screaming at Hammond, we’re not going to make it,” Waltrip said, indicated that his car started to sputter with two laps left. “And he’s screaming to me, just shut up and drive.

“So with the white flag in the air, we come by with one to go, and this thing is cutting out. It’s popping, it’s cracking, it’s picking up fuel in a straight line and losing in the corner, but for God knows why in some odd way, that thing had enough fuel in it that it made it all the way around that last lap.”

Hammond said at one point in the closing laps, Waltrip told him to get the gas man ready because he was coming to pit road. “We said no, you’ve got to keep going, run that son of a gun dry, because we’re committed,” Hammond said. “We were either going to live or die by whether Betty made it back to the start-finish line.”

Stevie Waltrip, meanwhile, was left double- and triple-checking her math, all while trying to remain calm.

“I’m sure if somebody had taken my blood pressure, it would’ve been sky high,” she said, “but I always liked to give the impression that I was not moved necessarily. Once I go in that direction, it’s not good. I was real excited and I could hear Darrell on the radio with Jeff, saying, ‘I’m running out of gas! I’m running out of gas!’ and Jeff’s telling him to draft. I was really grateful.

“Somebody came over to me on that last lap, I don’t remember who but they were celebrating, and I said, ‘don’t do that yet. It’s not over.’ Those are the things I remember. I just remember being so excited for Darrell.”

Darrell Waltrip’s animation stayed bottled up until just moments after the finish.

“It was the most dramatic, nerve-wracking, absolute I thought I was going to lose my mind race that I think I’d ever been in in my life,” Waltrip said. “It was not routine, not easy, not typical. It was an amazing accomplishment to be able to run that many laps in a car that really wasn’t that good, on a day that it was good enough to win, and that was all that really mattered.”

The interview and the ‘Shuffle’

Mike Joy interviewed Hammond and Stevie Waltrip in quick succession from the chaotic scene on pit road. All three had a sense of disbelief, from Hammond’s indication that the race had been won with a Plan B and Stevie Waltrip’s difficulty in finding the right words. After a quick break in the broadcast, Joy followed the celebration to Victory Lane, where the 42-year-old driver was having his own trouble comprehending what had happened.

“The best thing about it was, he climbs out of the car and we didn’t have to wait for a (full) commercial break to get to the winner, as often happens today,” Joy recalled. “So it was just pure, raw emotion. And he climbs out of the car and he starts talking and he grabs me, and he has that gleam in his eye that kind of let me know right then and there that I had lost control of this interview, which was fine. I was then a willing accomplice for whatever he wanted to do.”

What unfolded was Waltrip hugging team owner Rick Hendrick and shouting, “I won the Daytona 500! I won the Daytona 500!” grabbing Joy’s shoulders before returning to his incredulous state. “Wait, wait, wait. This is the Daytona 500, isn’t it? Don’t tell me it isn’t. Thank God!”

Joy, for his part, was more than eager to led the celebration roll.

“When it came to grandstanding Darrell had few if any equals, and this was his moment,” Joy said. “Instead of interrupting him or firing in the question or something like that, it was real easy to just let him enjoy the moment however he wanted to. It turned out to be memorable. Every can remember that. Anybody who saw that moment remembers it, and I don’t think there are — maybe Dale Earnhardt in ’98 — but I don’t think there are many Victory Lanes in the Daytona 500 that compare with that one.”

The customary radio interviews and Victory Lane photos followed, but Waltrip added his own special touch, borrowing a cue from a national phenomenon in another professional sport. The ephemeral rise of Cincinnati Bengals running back Elbert “Ickey” Woods had enlivened the NFL, briefly making him and his signature touchdown dance — the “Ickey Shuffle” — household names.

So Waltrip made the football two-step his own.

“People were trying to think of unique ways to celebrate their victory,” Waltrip said. “So they were asking me if you win the race, what are you going to do? I said, ‘boys, I ain’t got a clue, but I can’t wait to see because I’ll think of something. But I’m going to have to win it first and then I’ll think of something.’ That’s where the Tide Slide as I liked to call it, that’s where it was invented. That’s what I did and spiked my helmet.”

Lingering legacies

By the time Waltrip finally won the Daytona 500, his credentials for inclusion in the yet-to-be-built NASCAR Hall of Fame were well rooted. He was already a three-time champion of NASCAR’s premier series with a high perch on the all-time win list. Waltrip was also a four-time winner of the Coca-Cola 600; he’d get his fifth later in the 1989 season.

Even with all those accolades, the Daytona 500 had escaped his grasp. It only made his determination to achieve it greater, to fill that last remaining void on his driving record.

“The one thing you don’t want in your career is a ‘yeah but,’ ” Waltrip says. “You don’t want to say all the things you’ve done, and ‘yeah, but you’ve never done this or yeah, but you’ve never done that.’ As you go through your racing career, in particular as you get to the end of your career, you always hope and think, have I got any ‘yeah buts’ out there? Are there any things that I could’ve done, should’ve done, wish I’d have done that I didn’t get to do? And Daytona would’ve been a huge ‘yeah, but.’

“You’ve got all these things, won championships and all these races, but you’ve never won Daytona. That would’ve been huge.”

Hammond’s own legacy was already secure as crew chief for two of Waltrip’s titles, and his Daytona 500 triumph added to his eventual total of 43 premier series wins. But what he saw in his driver that day was the opportunity to finally breathe more easily.

“What I sensed at Daytona at the end of that race was a sigh of relief,” Hammond said. “I really do. I think it’s like, ‘man, I finally won the Super Bowl. I finally went the distance and was able to close it out in that ninth inning in the final game of the World Series.’ It’s that kind of an accomplishment. To be a part of that and to be so involved in his career from championships and to finally put that crown jewel at the top, and it was somewhat late in his career when he did it, I think it took the pressure off him to feel like now, I belong in the same league with Petty and Pearson. I think that was part of it.

“These drivers, when they’re able to hoist that trophy, it puts you in a very unique class and I think if he had never done that, I think it would’ve been something lacking. There would have been a certain hole in his legacy when it comes to being a Hall of Famer.”

Still together

When Waltrip retired after the 2000 season, he was among the first hired for to join FOX Sports’ all-new team for broadcasting NASCAR races the following year. Before he’d even settled in, he was heavily involved with FOX Sports management in selecting the on-air talent that would surround him. All would have their own ties to his day in Daytona in 1989.

Mike Joy was his first pick as the team’s quarterback. McReynolds and Hammond followed, as did reporters Steve Byrnes and Matt Yocum. The core group all worked together on a broadcast of an Xfinity Series (then the Busch Series) event before making their full-fledged national debut in 2001. It was enough to convince the FOX brass that they had made the right call.

“It’s kind of neat, isn’t it?” Joy says. “I think much in the way that sometimes in this business if you’re lucky, sometimes your heroes become your friends. Sometimes the people you cover end up becoming your colleagues and you develop quite a bond, and you look back to where it began and that was one of those times.”

McReynolds realized that the new on-air lineup was a special group early on, though he had his own apprehension about how their personalities would align.

“When you have a group of people and it’s a group of people that’s been successful and you’ve got them trying to work together, the biggest obstacle is egos,” McReynolds said. “And are you kidding me, egos? Mike Joy, Darrell Waltrip, Larry McReynolds, Jeff Hammond, and throw all the others in, that’s enough ego to fill a warehouse and start oozing out the cracks.

“But I think what we’ve all done a really good job at for going on 19 years is that the biggest part of our ego is to let’s just have a good broadcast. I think that’s one of the biggest components to make that work.”

Hammond said he was fortunate, not only to have played a large part in one of Waltrip’s signature wins, but in being able to make the transition with him to a new role in the sport after their racing careers were complete.

It’s a near-weekly get-together for the key players that made the 1989 victory in the Great American Race a reality. And all that reminiscing has Hammond eager to form another reunion soon.

“We have gotten together a couple different times to have dinner and drink a couple beers over that win,” Hammond says. “We probably need to think about doing it here with a 30-year anniversary. There’s still a bunch of us around and for those who aren’t, we need to remember them and we need to remember the moment that we all, that particular day … I wouldn’t say we were perfect, but we were perfect for the day.”

The post 17 ways to Sunday: Darrell Waltrip’s ’89 500 win, its freaky numbers connection and lasting legacies appeared first on Official Site Of NASCAR.

Leave a Comment